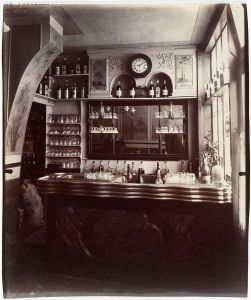

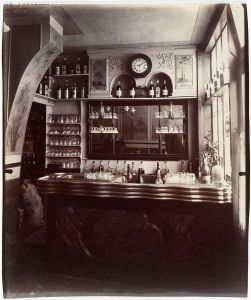

“Eugène Atget, Rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève, 1924” by Eugène Atget – Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 190040304. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Blake, Jody (1999). Le tumulte noir: modernist art and popular entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1930. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Haskins, James, & Duconge, Ada Smith (1983). Bricktop by Bricktop. New York: Atheneum.

Lloyd, Craig (2000). Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

Shack, William A. (2001). Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Stoval, Tyler (1996). Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Williams, Iain Cameron (2002). Underneath A Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall. London, New York: Continuum.

“You Americans take jazz too lightly. You seem to feel that it is cheap, vulgar, momentary…Abroad we take jazz seriously. It is influencing our work…I like jazz much more than grand opera.”

– Maurice Ravel (Letters, Interviews in Arbie Orenstein, A Ravel Reader (1990), p.390 and p.280)

The “Jazz Age”, as F.S. Fitzgerald penned it, really had two major metropolitan locations – New York and Paris, or to be a bit more precise: Harlem and Montmartre. The reasons for this and full exploration of how this cultural phenomenon came about has been recently documented in several books since 2000. To name but a few: William A Shack’s wonderful history Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars (2001) Published by the University of California Press. Underneath A Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall by author/biographer Iain Cameron Williams (2002) Continuum Press, London and New York. Author Jody Blake discusses the topics of jazz music and new movements in art in her illuminating social – cultural critique Le Tumulte noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1930, published by The Pennsylvania State University Press (1999). In addition to these insightful cultural histories of the period, there are two biographies of major African American entrepreneurs who helped to create the jazz explosion that so absorbed the city of Paris in the period between the two world wars: Eugene Bullard and Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith: CraigLloyd’s Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris (University of Georgia Press, 1999) and Bricktop by Bricktop co-written by Bricktop and James Haskins (Welcome Rain Publishers, 2000.) One of the most comprehensive books to describe the influx of black American musicians and writers who worked and lived in Paris is Tyler Stoval’s well researched history: Paris Noir, African Americans in the City of Light (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996).

1.5 million French youth were killed in World War I, and in addition another 740,000 were permanently disabled. “France suffered physically more than any other country, for most of the time war raged on French territory.” (Shack, 2001, p. 26) At the end of the Great War, the French were anxious to plunge into activities and interests far removed from the horrors of trench warfare. American culture and French culture were moving in new directions, and there was a large demand for a break with the past. Among the many influences affecting France’s new tastes in music were the famous Revue Negrè, which played at the Théâtre des Champs-Élyseès for three months in 1925 and Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1928 which came to Paris in 1929 to play the Moulin Rouge. Luminaries Josephine Baker and Sidney Bechet were stars of Revue Negrè whereas Adelaide Hall and Earl ‘Snakehips’ Tucker were in the Blackbirds Revue. Iain Cameron Williams reports in his biography of Adelaide Hall that when she arrived at the Gare St. Lazarre she was greeted by a reception of fans and reporters that was as large as Charlie Chaplins’s two years earlier. (Williams, 2002, p. 176) New music and new dance forms were sweeping through the metropolitan clubs, nightspots, and dance halls. Dances included the fox-trot, the grizzly bear, and ever-popular tango, and ragtime steps. “These developments in New York City had an immediate impact in Paris…” (Blake, 1999, p. 42) The art world of Paris embraced all things African, chic primitive and African-American culture was proudly displayed in the paintings of Francis Picabia Negro Song, Albert Gleizes Composition for “Le Jazz,” Gino Severini The Bear Dance at the Moulin Rouge, Marcel Janco Jazz 133, Marcel Vertes “Dancings: Le Jazz,” Yves Tanguy Bar Americain and a host of others by Picasso, Matisse, and Covarrubias. (Blake, 1999, pp. 42-57; color plates after p.136) While artists such as Jean Cocteau were embracing jazz music, the great composers of Europe were embracing it as well: Ravel, Stravinsky, and Milhaud were in the forefront.

“Eugène Atget, Quai d’Anjou, 6h du matin, 1924” by Eugène Atget – Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 190039851. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A great influx of American musicians, mostly African-American, either came to Europe or stayed in Europe after the Great War ended. The reasons were many, but first and foremost was the desire to live and work in a country that did not practice racial discrimination. Musicians also enjoyed the pleasant experience of being able to earn a living comfortably while developing their music. The demand for jazz was in excess to the number of musicians transplanted, and therefore economics were a compelling reason for staying or relocating to Europe. James Reese Europe and the Clef Club & Society Orchestra were in Europe in 1913 and 1914 (they played ragtime and fox trot numbers.) Jim Europe’s band had even played a “command performance” for the King of England in 1917. Sidney Bechet had toured with Will Marion Cook’s Syncopated Orchestra in 1919. The conductor, Ernst Ansermet, heard Bechet play with Cook’s ensemble and was amazed by his musicality. The Harlem musicians who came to Paris were pleased with the affordable housing available to them in the Parisian area known as Montmartre. They also appreciated its artistic and bohemian atmosphere. One of the first nightclubs that began was Le Grand Duc which opened its doors in 1921. It was owned by Eugene Bullard, an African-American from Georgia who had been a combat aviator for France during the WWI and had earned a living in boxing in the United Kingdom. Another famous expatriate from Harlem, ‘Bricktop’ (Ada Smith) started her career in Paris giving Charleston lessons to patrons of Le Grand Duc. It was the new dance craze which all the society people wanted to learn. William A. Shack tells us in his book that another famous American who worked there was Langston Hughes who washed dishes for the club and who convinced Bricktop to stay when she first arrived but was dismayed at how small the club was compared to famous Harlem nightclubs such as Connie’s Inn (Shack, 2001, pp. 53-54). Small or not it was the place to be in the evenings where one might run into Elsa Maxwell, Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, Sophie Tucker, the Prince of Wales, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway.

Another legendary nightclub in the City of Lights was the famous Le Boeuf. William A. Shack lists some of its patrons: Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Rene Clair, Marcel Duchamp, Max Jacob, Eric Satie and Maurice Ravel, who was a bit of a night-owl (Shack, 2001, p. 50). As the author recounts Le Boeuf, when it was located on the rue Boissy-d’Anglas, had “the loudest jazz, the prettiest women, and the latest art gossip to be found in Paris.” (Kluver, Billy, and Julie Martin: Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers 1900-1930. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989, p. 80.) The legendary nightspots of Paris: the Rotonde and the Coupole on le Carrefour Vavin (which featured large ballrooms), the Jockey (famous for jazz), and the Jungle (live or recorded jazz); both small clubs were started by American painter Hilaire Hiler. People danced to blues on a tiny dance floor. The night spots of Montmartre: the Abbaye Thélème, Bricktop’s, Chez Forence (named after singer Florence Embry), the Grand Duc, the Perroquet, the Plantation and Zelli’s – all Harlem style night clubs featuring the jazz one would hear in Harlem. These clubs were popular with the Dadists of the early and mid-1920s. The Tempo Club which was a hangout for the members of the Southern Syncopated Orchestra and their friends. “The Tempo Club and the Grand Duc were where African-American entertainers came to dance and make music for their own enjoyment…” (Blake, 1999, p. 113). Langston Hughes recalled in his autobiography, The Big Sea, how all the musicians and entertainers from the smaller clubs would come to Le Grand Duc after their clubs had closed to play in ‘jam sessions’ way into the early morning hours. This was in 1924, “only in 1924 they had no such name for it. They’d just get together and the music would be on.” (Langston Hughes. The Big Sea, New York, 1940, pp. 161-162.)

“Café, Avenue de la Grande-Armée, 1924–25” by Eugène Atget – Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 190036464. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Living Legends: ‘The Stuff that Dreams are Made of…’

If there ever was a living equivalent to “Rick” (of Rick’s American Café in the film Casablanca) it would be Eugene Bullard whose life is well chronicled in Craig Lloyd’s biography of the musician, boxer, and café-owner as well as in William A. Shack’s Harlem in Montmartre. Both authors describe how Bullard was a famous boxer (he knew Jack Jackson), a French combat aviator in World War I (he was awarded the Croix de Guerre), befriended American writers and jazz musicians and provided them jobs in his nightclub (he hired Langston Hughes straight off the boat from New York), and gave Ada Louise Smith ‘Bricktop’ her first job when she arrived in Paris. When the German army invaded Paris in June 1940 Bullard chose to stay in Paris where his night club was frequented by the Nazi commanding officers, Corsican gangs, and members of the French resistance. Information flowed to the resistance which benefited them in their sabotage of the invading army. Famous musicians who played in the Paris nightclubs during the Nazi occupation included Django Reinhardt (Stephane Grappelly thought he was nuts to return to France since the Nazis were sending gypsies to their concentration camps), Arthur Briggs whose orchestra performed at a Champs-Elysees nightclub, pianist Maceo Jefferson, and Harry Miller the guitarist and singer who entertained at the American Legion Bar (Shack, 2001, pp. 109-110). When his friends finally convinced Bullard to leave Paris for his own safety, he helped the French resistance install machine guns on the left bank of the Loire River to fight the Germans. In the pursuit of these efforts Bullard was wounded and had to be treated in a hospital before he could finally leave France from Biarritz. (Shack, 2001, p. 110) Musician friends of Eugene Bullard during his two decade history of being a Paris nightclub owner included Sidney Bechet, bandleader and fellow club-owner Joe Zelli, Ada Smith, jazz drummer Buddy Gilmore and others. A pianist who played for him in his club was Arthur “Dooley” Wilson who went on to form his own band had bookings in Europe and North Africa. Arthur “Dooley” Wilson played the role of “Sam” who sang As Time Goes By in the 1942 movie Casablanca. (Lloyd, 2000, pp. 92-93) In fact, many black Americans also chose to stay in France although it was dangerous. This was sometimes due to the fact that these musicians had families they had started with their French wives and they decided to be with their wives and children rather than trying to relocate back to the United States. Two such musicians were Arthur Briggs and Charlie Lewis. Later they are arrested by the German authorities who kept them under detention (Lloyd, 2000, p. 116).

“Eugène Atget, Marchand de Vin, Rue Boyer, Paris, 1910–11” by Eugène Atget – Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 190039516. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Life Abroad and Life at Home

Author Tyler Stovall describes in great detail the development of jazz in Paris and the personalities who made a living playing their music in the City of Light during the Jazz Age. He documents the efforts of some black soldiers after the Great War to remain in a country which they felt did not discriminate against color or race. Some of them enrolled in the Paris universities in order to remain legally in the country, but others chose to earn a living as entertainers. (Stoval, 1996, pp. 68-69) For the musicians who chose to stay in France, Montmartre offered an environment free from the racial problems back at home as well as a thriving community of art, literature and music. The author describes in great detail the various night clubs in Montmartre that flourished in the 1920s and offered jazz music to Parisians thirsty for this exciting new music. He also acknowledges the dangers of living in the bohemian section of Paris and how on occasion musicians such as Eugene Bullard, Louis Mitchell and Sidney Bechet had to resort to carrying firearms for protection. “Corsican protection rackets infested the neighborhood, demanding and usually getting money from club owners who wanted to stay open. Eugene Bullard got into a vicious battle with one such gangster named Justin Pereti, who ended up shooting him, putting him in the hospital.” (Stoval, 1996, p. 43) In the 1930’s more and more American jazz musicians came to Europe and played music along with European musicians. Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter performed and recorded alongside European players such as Django Reinhardt and Stepane Grappelli. Harlem musician (he played in the band at the Savoy Ballroom) Bill Coleman was a talented trumpet player who visited France several times. He lived in Montmartre and was featured in French jazz orchestras. Another swing trumpet-player Arthur Briggs married a French woman and settled down in Paris. Author Tyler Stoval describes in great detail the lives of these black American musicians who made Paris their home. In fact, Paris included other black entertainers such as blues singer Alberta Hunter, pianist Ray Stokes, trumpeter Harry Cooper, and Opal Cooper who sang at the Melody Bar (Stoval, 1996, p. 117).

‘Blackbirds’ Comes to Paris

Some African-American artists did not remain in Paris after their tour was over. Adelaide Hall was a tremendously talented singer, dancer and entertainer who came to Paris in 1929 with Lew Leslie’s revue Blackbirds or Les Oiseaux Noirs. It was booked for a limited engagement at the Moulin Rouge and she and the cast returned to the United States for the U.S. tour when it was over. In his book Underneath a Harlem Moon Iain Cameron Williams gives a vivid picture of her life in America, where she encountered racist abuse and harrasement all too frequently, and her twelve-week stay in Paris where she was universally admired and adored. What an incredible disparity between cultures! It is a wonder that Adelaide Hall and her husband did not choose to remain in Paris, although they probably thought about it. The author includes detailed verbatim racial abuse she and her husband Bert Hicks suffered while touring the United States where discrimination, segregation and racial bigotry reined (Williams, 2002, pp. 257-259; 265-280) In Paris the singer-entertainer lived a life of enjoyment and wonder where she could sleep until noon, have a leisurely breakfast and set off in the afternoon to shop in some of Paris’s finest establishments before heading to her show in the evening. The cast and crew of Blackbirds would visit the cabarets and nightclubs of Montmartre when their show finished for the evening , and they were welcomed in all the local restaurants and private homes. They were given so many gifts by admirers that they had twice as much luggage to declare when they returned to New York on the SS Ile de France. However, in 1935 Adelaide Hall and Bert returned to Paris, and were immediately welcomed by a surprise party for the couple at Bricktop’s establishment on rue Pigalle (Williams, 2002, p. 313). Adelaide Hall told admirers over French radio that she had returned to Paris with an intention to stay. She even sang one song over the airwaves in French to show her appreciation (Williams, 2002, p. 313). Her engagement at The Alhambra was the big hit of the season and she was surrounded by jazz musicians and friends from America, Paris, and England. She was reunited with her former pianist, Joe Turner, and they even recorded several songs for Ultraphone including Truckin’, I’m In The Mood for Love, Solitude and East of the Sun West of the Moon. Violinist Stephane Grapelli was in the band on these recordings (Williams, 2002, p. 313) Adelaide Hall was the involved in several business ventures in Paris in the 1930s and she was a co-owner of her own night-club – the Big Apple which opened on December 9, 1937 at 73 rue Pigalle. The bandleader was Maceo Jefferson, and there were live radio broadcasts from the club on Saturday nights which could be heard throughout Europe (Shack, 2001, p. 97).

Legendary Cabaret Owner ‘Bricktop’

A major document of the period is, of course, the autobiography of the very famous nightclub owner, Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith who sat down with James Haskins in the 1980s to write Bricktop by Bricktop. By many people’s accounts Bricktop’s was the most Harlem-like nightclub in Montmartre or all of Paris. Bricktop knew just about everyone in music business in Paris (and, for that matter, in New York as well.) She was friends with Cole Porter, Noel Coward, Mabel Mercer, Duke Ellington, F.Scott Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, Jack Johnson, Gloria Swanson, Django Reinhardt and literally hundreds more. She named her club after herself at Cole Porter’s suggestion. Django Reinhardt was hired to play at her club when others would not book him. Mable Mercer sang at her club. Bricktop was one of the most well-known and well-liked celebrities in Paris. She was also one of the most well-respected business persons in Paris when she was there. People sought out her advice on any and all aspects of running a restaurant, nightclub or cabaret. She freely lent her expertise to all who sought her help, and for this reason even her competitors admired her. While she was friends with the rich and famous, including royalty such as the Duke and Duchess of Winsor, she never placed anyone over anyone else. She treated all people as people worth knowing, and for this reason, many guests at her establishment felt she was the ultimate hostess. She did not consider herself a singer, “I’m a performer and saloon-keeper” is how she referred to herself (Williams, 2002, p. 312). Bricktop’s first job in Paris was working for Charles Bullard at his club Le Grand Duc. While employed there in 1925 she met and befriended Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Cole Porter heard her sing one of his songs and asked her if she could show him how to dance the Charleston…soon the two of them were organizing Charleston parties for Cole’s friends (Stoval, 1996, p. 45). In Bricktop’s autobiography she describes how much she liked F. Scott Fitzgerald even when he arrived drunk or broke. Fitzgerald introduced Ernest Hemingway to Le Grand Duc but Bricktop did not find Hemingway very likable – “he just wanted to bring people down, and he had a way of doing it, and he was liable to punch you at the same time” (Haskins & Duconge, 1983, p. 98). When Bricktop opened her own nightclub in Montmartre, Cole Porter brought his friends to see her new establishment, and the club became popular overnight. Guests included George Gershwin’s favorite singer Helen Morgan; the world famous violinist Jascha Heifetz was a frequent visitor and he enjoyed listening to the young woman violinist that Bricktop had hired to play. (The violinist practically fainted when learned the identity of the distinguished patron.) Elsa Maxwell and Irving Berlin were also visitors to her club. Jazz was the club’s specialty because Bricktop wanted to have the same sound one could hear on any given night in Harlem. When Duke Ellington came to Paris in 1933 naturally he came to Bricktop’s. The same night that Duke Ellington and members of his band came to visit, Bricktop’s other guests included Josephine Baker, Spencer Williams, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr as well. As it turned out, they all shared the same table and got to know each other well (Haskins & Duconge, 1983, pp. 186-187). Mabel Mercer was one of the greatest chanteuses of the twentieth century. Bricktop hired her to sing at her club. Song writers went out of their way to write material for Mabel Mercer since she could interpret a lyric so well. With the inclusion of Mabel Mercer in her club, Bricktop managed to create the ambiance of café society within the larger environment of a Harlem-style night club. This of course was perfect for Montmartre and fit the culture of Paris to a tee.

When Bricktop chose to leave Paris in 1938 and her establishment closed, Adelaide Hall continued the tradition of a Harlem-style night club by opening her own club The Big Apple. On any given night one might catch Maurice Chevalier and Marlene Dietrich, who were friends, at the new night spot. Adelaide’s financial backer for the club was Hetty Flacks, and Adelaide’s husband, Bert Hicks, was the proprietor. Fats Waller dropped in one night and played “an hour-long duet with Adelaide” to the excitement of the patrons (Williams, 2002, p. 352). Author Iain Cameron Williams writes of the Big Apple, “The music was blisteringly hot, arguably the best outside of America, and any black musicians in town would make a beeline to the venue to jam with the combo (Williams, 2002, p. 352). To add to the excitement of this establishment was the fact that there was a live radio broadcast from the club on Saturday nights which could be heard throughout the continent (Williams, 2002, p. 353). Sadly, an end of an era was fast approaching.

Philosophy, Art, Popular Culture

Art historian, Jody Blake informs us that many of the leading intellectuals and artists of Paris in the Jazz-Age were using jazz music as a metaphor and in fact perhaps did not fully understand or appreciate the music in itself. As an argument against the prevailing culture of the preceding decades they were inspired by a music and an artistic endeavor which they viewed as radically different. Jazz was such an inspiration that it helped to define new approaches to their own artistic endeavors. However, it is also clear that many of the Dadists really viewed jazz as chaos and cacophony and as opposed to being music. They admired endeavors which they felt threatened bourgeois sensibilities.

Jody Blake, who is the curator for the McNay Art Museum San Antonio, points out that eventually the Dadists and some of the other early supporters of jazz music turned against it, and they saw it as a threat to their own culture and to the supposed norms of their long tradition of classical music and harmony. Once this happened they became ardent opponents of the black artists and entertainers who were making a living in Paris, and they tried hard to instigate a huge public reaction against the new music which came to their county. They championed the popular bal-musettes as the truly French music and they insisted upon a return to nationalistic identity in popular music. Certainly, they had public taste on their side as French music employed instruments such as the accordion, violin, and even bagpipes – instruments which at that time seemed incompatible with developments in jazz. French theorists and intellectuals turned conservative and even denounced the new forms of entertainment a degradation of morality and destruction of societal norms. (Blake, pp.101-107)

Philosophy and Art sometimes inform us of cultural trends and sub-currents in ways that history and biography cannot. This is why Jody Blake’s cultural history and critique, Le tumoult noir, is essential to an understanding of the culture of jazz in Paris in the era between the two world wars. The French had been subconsciously preparing themselves for an acceptance of jazz and African-American culture for several decades. The process was as much subconscious and archetypal as it was intentional. There were sub-streams in French culture that French writers, impressionists, and post-impressionists had tapped into around the fin de siècle, and which burst through into the twentieth century as black artists, writers, poets, and musicians began their sojourn in France. Jody Blake’s book serves to inform us of those cultural currents and thought processes that eluded even most of the participants of the Jazz Age in Paris while they were living it and creating it. People respond to art and music in a very subconscious way. A painting or a song or a piece of music may affect us in a way which we do not fully understand. The artists who were living and working it Paris, and especially Montmartre, in the years leading up to the ‘jazz age’ were blending and exploring new forms of artistic expression which they were appropriating from cultures from Africa, South America, Asia and America. Jody Blake’s book describes this process and the artists who were shaping the new trends in French culture.

Concluding Remarks

Beginning around the new millennium (circa 1999, 2000) several writers, biographers, sociologists, historians, and jazz chroniclers felt that it was time to record the history of jazz in Europe, and more specifically in Paris in the days of the early twentieth century. Authors Tyler Stoval, Iain Cameron Williams, William A. Shack, Craig Lloyd, Jim Haskins and Jody Blake wrote and published interesting and compelling histories of the men and women who brought jazz to Paris and thereby to Europe. Adelaide Hall, Sidney Bechet, Eugene Bullard, and Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith, Will Marion Cook, James Reece Europe, Arthur Briggs, and Bill Coleman were but a few of the creative and fascinating personalities and talent who ‘conquered’ Paris with an energizing new form of music. Their contribution was to take hold and inspire a whole new generation of talented European musicians. When American jazz musicians were to travel to the continent in succeeding decades to play concerts there was no lack of native born talent to help them perform. Whether it was Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington in the thirties, the swing bands in the forties after the war, or Charlie Parker and Bud Powell in the fifties, Dexter Gordon and Eric Dolphy in subsequent years – American jazz musicians could find plenty of skillful and creative European musicians to play music with and to form bands. American musicians began to relocate to Paris, Stockholm, Denmark, and Italy knowing full well that they could live well and play creatively in Europe. When Django Reinhardt toured the United States with the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1946 there quietly began a new era, the acknowledgement that European musicians were now influencing American jazz music and the future of jazz. It turns out that the French intellectuals who feared that American jazz would eclipse their culture had nothing to worry about – in fact, it was just the opposite – Django and the Hot Club of France were creating a unique European hybrid which was, in its turn, influencing the development of jazz music in America and in the U.K.

The subject of Paris in the Jazz Age is too rich and variegated to be fully captured in any one book as brilliant and as well-researched as it might be. Each of these fairly recent books is well-documented and rich in detail. The authors have presented their subjects with amazing insight and clairity. Each book, therefore, serves to inform and enrich the others. It is interesting that many of the stories told in one volume may appear in a slightly different presentation in another. It is sort of like reading Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet in that the personages described as having lived and performed in Montmartre in the 1920s and 1930s were all larger than life, and their stories and lives cannot be reduced down to one understanding of who they were or what they did. The more that each one of these books is consumed by the reader, the more one gets a fuller, more complete, and to some extent, more complex understanding of the era and the artists and musicians of that era. And what a brilliant era it was! Tyler Stoval does us a great favor by continuing the story through the 1940s, 50s, and 60s as well as he traces the lives of the original black artists, musicians and writers of the jazz era in Paris, and also introduces us to the newer generation of African-Americans who made Paris their home. People such as Richard Wright and James Baldwin to name a few. And who doesn’t want to know what happened to Arthur Briggs when he was arrested by the Nazis in 1940? Well, Professor Stoval continues his story and the stories of others who chose to live in France after the fall.

When Maurice Ravel toured the United States in 1928, he told Americans everywhere he visited, “I like jazz much more than grand opera…”(Arbie Orenstein, Letters in Ravel Reader, p. 280) You Americans take jazz too lightly. You seem to feel that it is cheap, vulgar, momentary. In my opinion it is bound to lead to the national music of the United States. Aside from it you have no veritable idiom as yet. Most of your compositions show European influences…”(Orenstein, Ravel Reader, p. 390) Abroad we take jazz seriously. It is influencing our work…” (Orenstein, Ravel Reader, p. 390)

Suggested Listening

Arthur Briggs

Avalon (Rose/Jolson/deSylva) recorded 1935. Michael Warlop & his orchestra. Coleman Hawkins (tenor sax), Django Reinhardt (guitar), Arthur Briggs (trumpet). Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Toute le Jour Toute la nuit (Cole Porter/L. Hennevé) recorded 1935. Alain Romans and his Orchestra of the Poste Parisien. Arthur Briggs (trumpet), Leon Monosson (vocal), Michel Warlop (violin), Django Reinhardt (guitar). Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Django Reinhardt

Darling Je Vous Aime Beaucoup (Anna Sosenko) Recorded 1935. Jean Sablon (vocal), Stephane Grappelli (violin), Django Reinhardt (guitar) Rare Django, « Disques Swing » DRG Records Incorporated.

Out of Nowhere (Green/Heyman) recorded 1937. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Mabel Mercer

While We’re Young (Alex Wilder & Bill Engvick) The Art of Mabel Mercer, Altantic 2-602

Hello Young Lovers (Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein) The Art of Mabel Mercer, Atlantic 2-602

Feuilles Mortes “Autumn Leaves” (Jacques Prevert & JosephKosma) The Art of Mabel Mercer, Atlantic 2-602

Adelaide Hall

East of the Sun West of the Moon (Brooks Bowman) Authentic Recordings (1932-1939)

Solitude (Duke Ellington, Irving Mills, Eddie Delange) Authentic Recordings (1932-1939)

Bill Coleman

Rosetta (Hines/Woode) recorded 1935. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Stardust (Carmichael/Parrish) recorded 1935. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

The Object of my Affection (Tamlin/Poe/Grier) 1935. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Bill Coleman Blues (Coleman) 1937. Bill Coleman (trumpet) and Django Reinhardt (guitar). Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Benny Carter

Out of Nowhere (Green/Heyman) recorded 1937. Trumpet, Benny Carter. Guitar, Django Reinhardt. Tenor Sax, Coleman Hawkins. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Coleman Hawkins

Honeysuckle Rose (Fats Waller & Andy Razaf) Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

Out of Nowhere (Green/Heyman) recorded 1937. Django and His American Friends, Vol. 1 & 2, BGO Records, BGOCD249, 1994.

![Portrait of Nat King Cole, New York, N.Y., ca. June 1947. William P. Gottlieb, photo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://music6cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/4843738572_59dc931b24_z.jpg?w=300)

![William P. Gottlieb [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://music6cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/52nd_street_new_york_by_gottlieb_1948-1.jpg?w=300)

![Maxine Sullivan, Village Vanguard 1947. William P. Gottlieb [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://music6cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/4843145591_d3d8a88c44.jpg?w=300)

![Frank Sinatra. William P. Gottlieb [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://music6cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/4843758568_85cb4e6c3e_z.jpg?w=293)

![[Portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov. 1946] William P. Gottlieb [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://music6cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/4843742660_02e0cc5189_z.jpg?w=289)

You must be logged in to post a comment.